Cover photo: Silhouette of People by Keith Wako

Malawi is stuck. Among the five poorest countries at independence, in 2021 it was ranked second from the bottom globally. Its vital statistics read like a bad day on the Somme.1

Its per capita income is $390, a quarter of the sub-Saharan average, itself seven times less than the global average. Malawians were very poor at independence in 1964, their average income just 5% of the global average; today they have unimaginably slipped further backwards to a paltry 3.5%. Put differently, Malawians are nearly 30 times poorer than the average global citizen, an astonishing statistic when one contemplates its development advantages (a lake covering one quarter of its total area and rich agricultural land) and how well we understand development choices, challenges and options by now.

Following independence, Malawi’s growth patterns initially tracked those of sub-Saharan Africa, increasing at 3.7% annually. Since 1980, however, it started to fall behind the rest of the continent, by then hardly a stellar performer. Malawi’s real per capita GDP grew at an average of just 1.5%, for example, between 1995 and 2015, well below the 2.7% average in non-resource-rich African economies.

There are few countries as poor that are not in war. At least Malawi has that going for it. To add insult to injury, Malawi has remained vulnerable to episodic financial crises, characterised by balance of payment issues, forex unavailability, rising inflation, high debt levels and a collapse in growth rates. Why is Malawi so poor, and why the recurrent tendency to crisis and constant slipping further backwards?

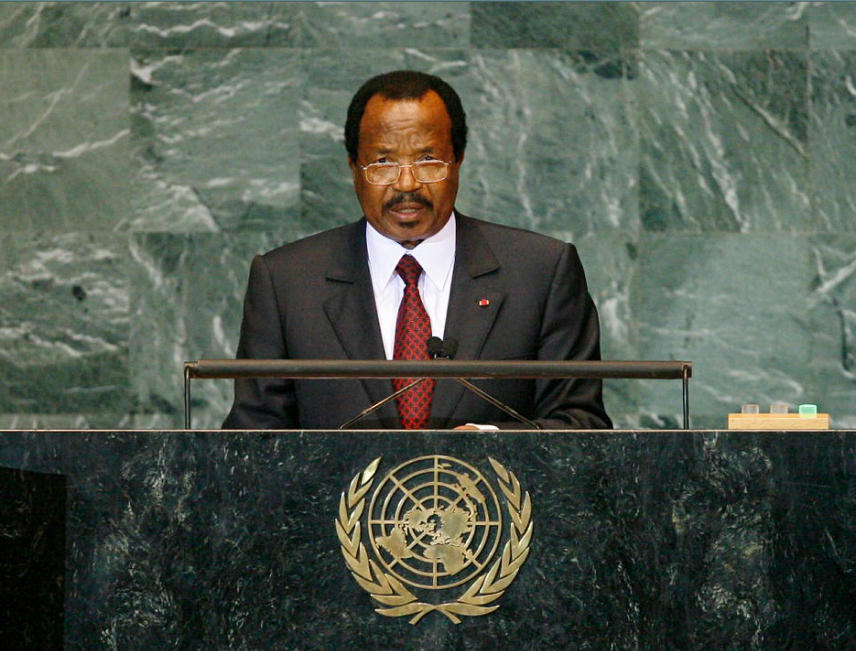

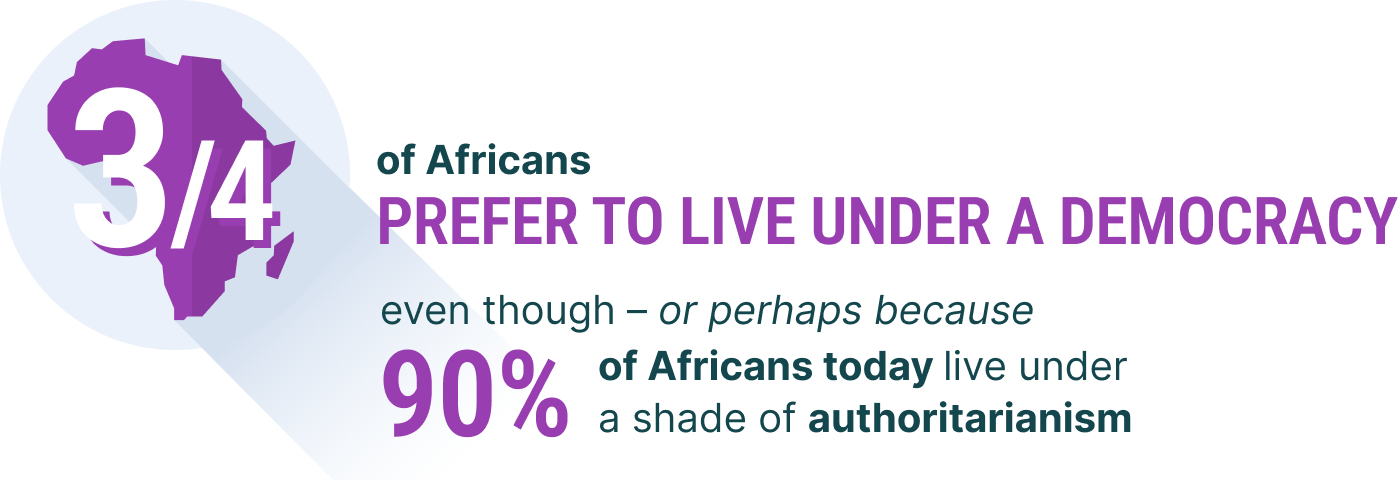

This is a result of many factors, of course. Many Malawians emphasise a combination of the poor colonial inheritance, being land-locked, poverty and unfavourable terms of trade. Others would prefer to point to the harsh regime of Kamuzu (Hastings) Banda, the Scottish educated authoritarian who ran the country with an iron fist until the advent of multi-partyism in 1994 – although Malawians are divided in their loyalty over the legacy of a man who referred to his own people as ‘children in politics’.

Even though things started to fall apart during Banda’s rule, especially by the late 1980s, forcing the arrival of the World Bank and imposition of a series of pro-market reforms, and growth was low, he was feared and, as a consequence, remains revered.

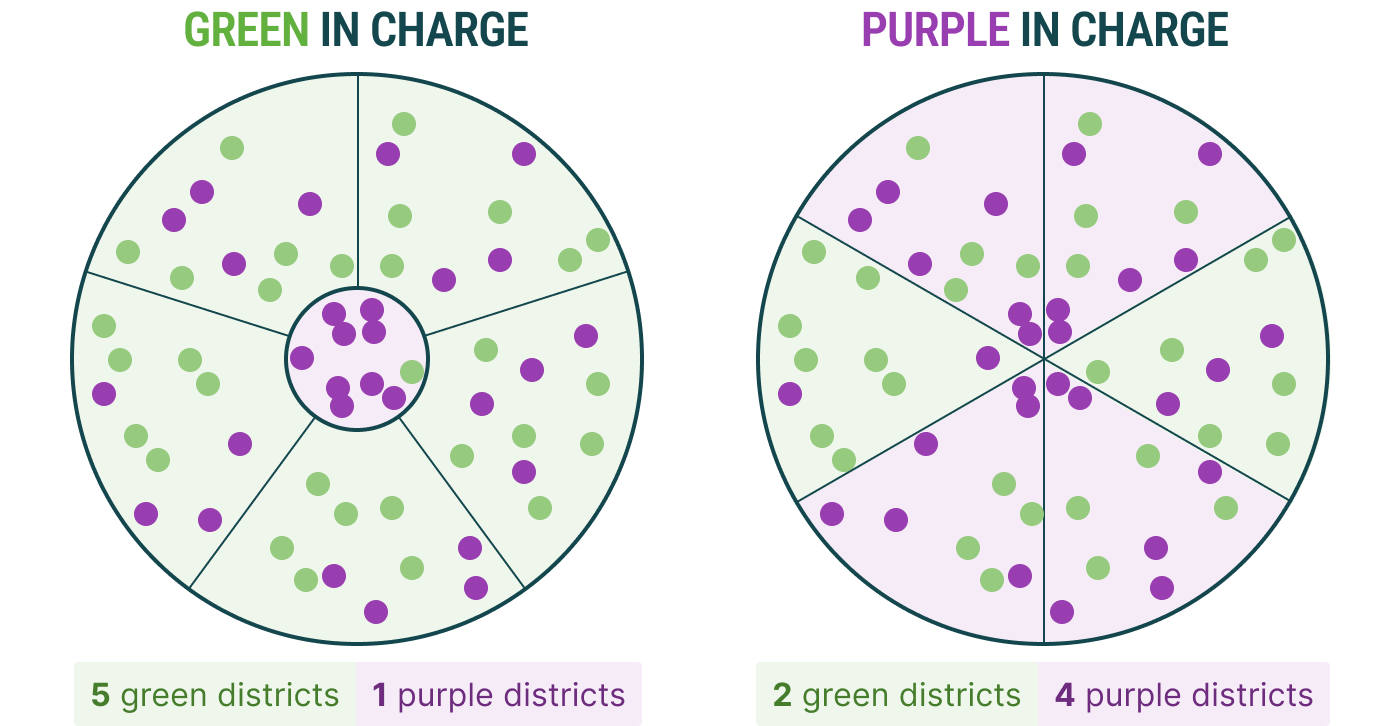

Banda’s brand of big-man politics highlights a consistent element over the last six decades: the poor choices made by leadership and the corrosive nature of governance. It’s not that Malawi lacks governance, but that the purpose of government is to enrich an elite at the expense of the poor. What this boils down to is the preference for a political pact among the elite to extract rents – even to the extent by driving macro-instability. According to this argument, there is no consensus to grow the pie for all. Instead, it is shared among the few. This is substantiated by the resistance to securing a proper rail network (acting in the interests of a transport mafia), the resistance to land reform (keeping the people poor, and elite interests secured), the resistance to reform fertiliser subsidies (for those who sell and distribute) and in the variety of state intermediaries in almost every area of the economy, from tobacco auction houses to buying agents for maize.

In each of these areas there are rents to be protected and constituencies to be maintained. This argument is used to explain why the government has retained the middle-man-style of state intervention in the economy when this had, even by the end of the supposedly relatively prosperous 1980s, proved unwieldly, to the point that the government had to seek assistance from the World Bank. It also clarifies why Malawi keeps going with agriculture input subsidy schemes and bucking regional market opportunities, and why the civil service is comparatively large (at 180 000), yet guided less by performance than loyalty and a pernicious ‘per diem’ culture of allowances to augment low salaries.

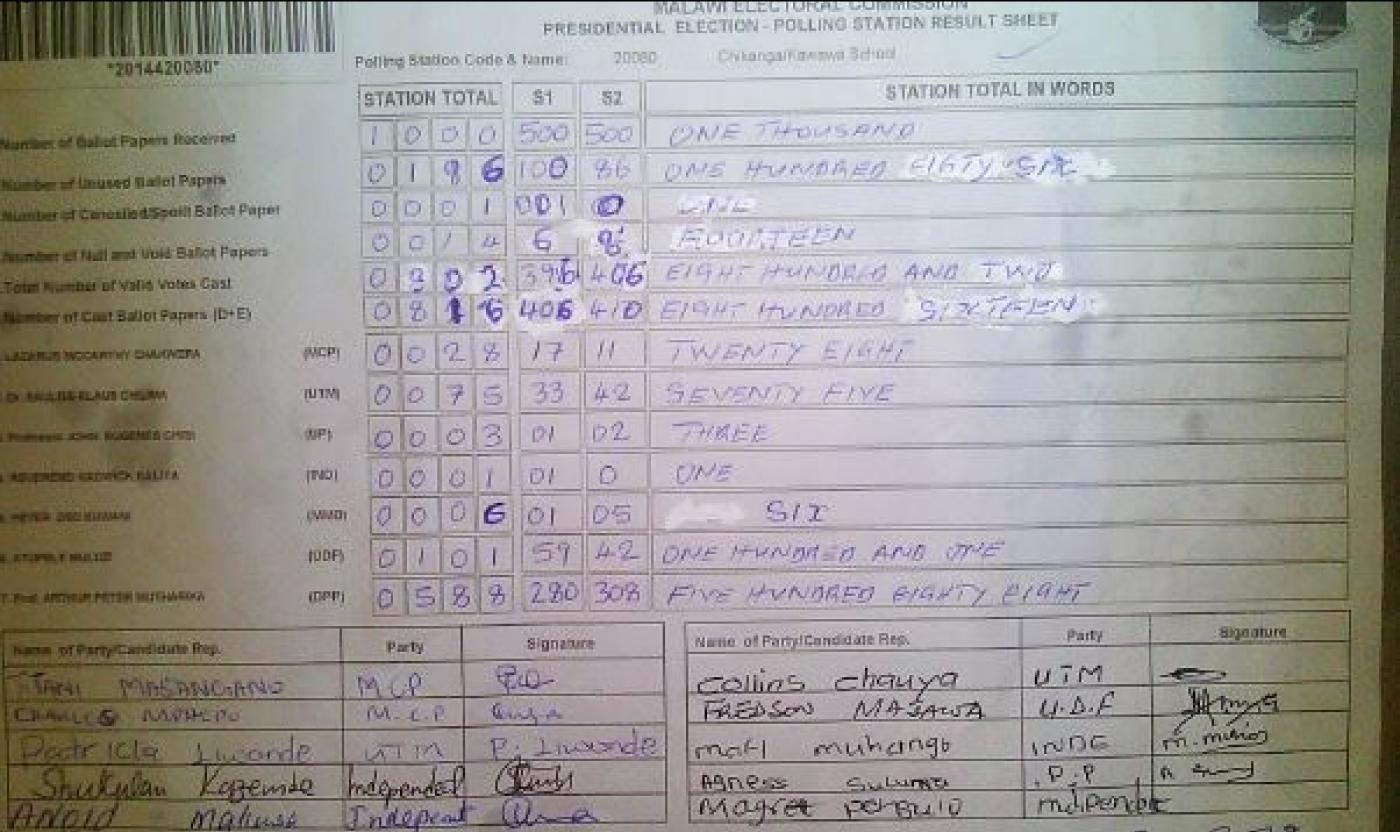

The greatest achievement of the ten years of government of Bakili Muluzi was the transition to democracy in 1994. His tenure, marred by corruption allegations and a maize shortage, could at best be described as a kinder, nicer version of Banda’s three decades of harsh rule, but also absent its governance and probity. Muluzi’s hand-picked successor, Bingu wa Mutharika (born Brightson Webster Ryson Thom), may have looked like a reformer and someone who understood, at least on paper, the laws of economics, given his years as the Secretary-General of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), but he proved an erratic president. His attempts to increase food security and maize output in Malawi through subsidisation of inputs resulted in a massive increase in production, but also fuelled corruption and diverted funding from other areas. Nationwide protests in 2011, sparked by worsening fuel shortages, rising prices, government waste (including the purchase of a presidential jet) and high unemployment, saw a violent crackdown as Mutharika said he would ‘smoke out’ his enemies. This only worsened the forex and fuel shortages as the donors withheld funds. After Mutharika died of a heart attack, a palace coup, led by his brother Peter Mutharika to attempt to sideline Binu’s estranged vice president, Joyce Banda, failed, and she became president in April 2012. Impressive early reforms to stabilise the currency, normalise international relations and cut back on excessive expenditure were overtaken by the ‘Cashgate’ government corruption scandal, and she easily lost the 2014 presidential election to Peter Mutharika. In a similar pattern to his predecessors, Mutharika’s term was marked by popular discontent, with food and power shortages and allegations of corruption. His victory in the May 2019 elections was widely disputed, with widespread tampering of results leading to the moniker the ‘Tipp-Ex Election’. Following the application of the opposition Malawi Congress Party (MCP) and United Transformation Movement (UTM) to the High Court to have the results set aside and conduct another election, the Malawi Constitutional Court ruled to nullify the election, ordering a fresh election to be conducted in 150 days. Mutharika only obtained 40% of the vote and was defeated by the MCP’s Lazarus Chakwera. However, Chakwera’s term took a long time to get into its stride, with little progress on necessary key reforms and being worn down by mounting corruption scandals.

How can this repeating cycle of ‘early promise followed by corruption and crushing disappointment’ be broken so that Malawi progresses in a way to assist its growing ranks of people lift themselves out of poverty? Can outsiders help?

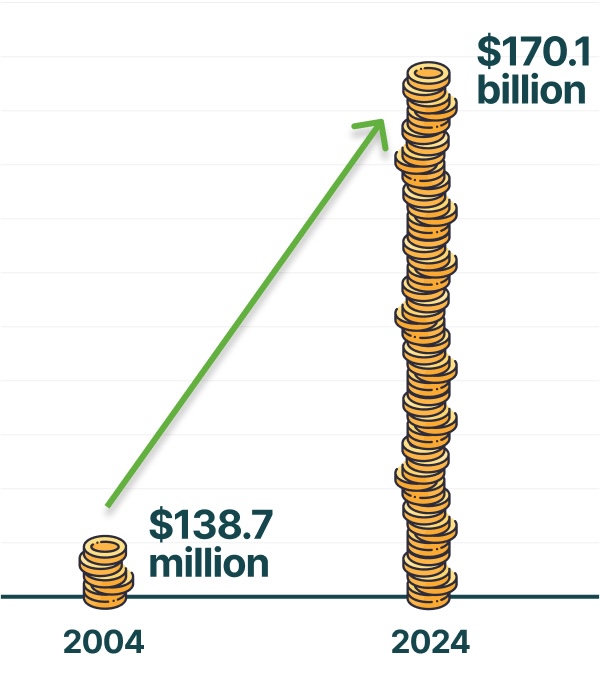

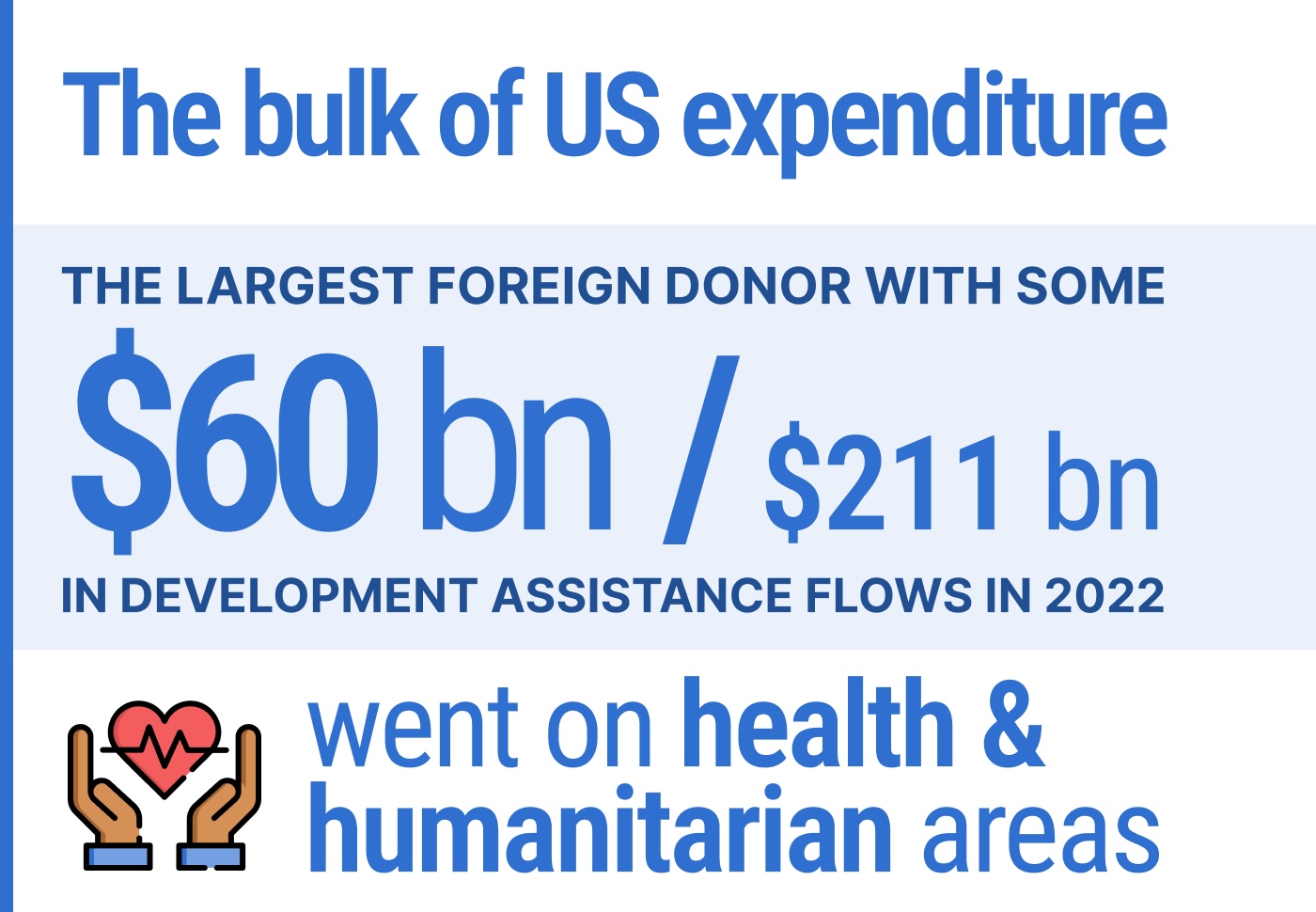

Here there are several schools of thought, dotted on a spectrum of optimism. One is that this can never happen, and that donors, among others, are simply compounding the problem. The evidence for this is that the $26 billion spent in donor funding since 1964 has failed to change the system of governance and cyclical, locked-in poverty (low income, weak public finances, poor education and health, limited infrastructure, low investment and low growth). Rather, to the contrary, it has encouraged rent-seeking behaviour and disincentivised reforms by providing a safety net. While the donors argue against this – in part because turkeys seldom vote for Christmas, and because there are valid humanitarian concerns about cutting off aid – the evidence suggests that, at best, donor spending has made things ‘less bad’.

Another version of this ‘development through aid’ argument is that you need more donor money – that the current $1 billion annually to Malawi is too little to make a difference, and simply offers a Band-Aid for what is a sucking chest wound in developmental terms. The dangers in this approach can be seen in the catastrophic failure of projects to prove this argument, including Jeffrey Sachs’ failed Millennium Village schemes, which operated at two sites in Malawi.

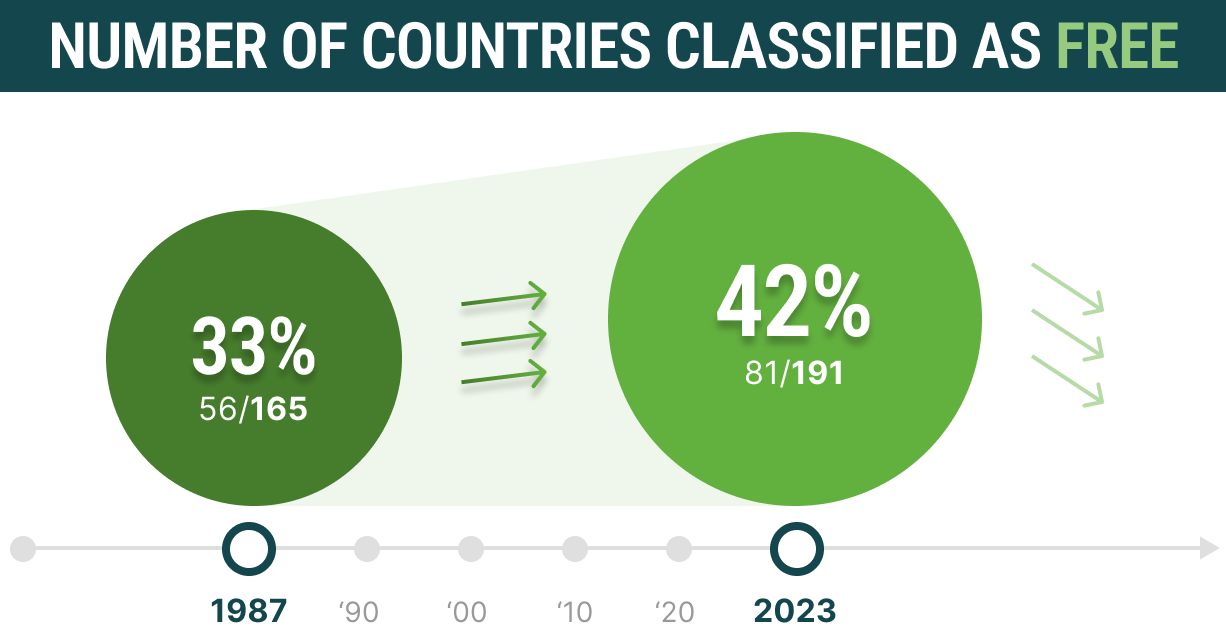

A third is that change is possible, and one has to look for green shoots in Malawians themselves, in the judiciary (which held the line against the regime of President Peter Mutharika in the election re-run), in NGOs and in the private sector.

In many other areas, externally driven efforts to reform have created incentives for actors to establish the form – but not the function – of institutions, while undermining the voice of domestic reformers. External pressure has created a ‘Newtonian’ reaction on the part of domestic reformers, with them moving in the opposite direction, a tendency fuelled by populist instincts and easy answers. Managed badly, too much pressure can cut off dialogue and upset relationships – and without a trusted messenger, there can be no message.

By starting small, strengthening local voices in the places where change is needed, and by sticking with it over a long time, the most desperate and seemingly impossible of circumstances can be changed. If outsiders can do this and avoid amplifying their own voices to advance their own careers and interests, then trust can be enhanced, and progress made.

In Malawi, this requires a leadership capable not only of pinpointing the problems, but prioritising and executing the solutions, being able to avoid self-defeating (if populist) economic choices (such as the land reform act, which effectively takes away land from foreigners, or banning the export of maize), and being willing to let go of control – or at least share in the benefits of change.

1 This section is based on a research trip to Malawi in January 2023, during which time the interviews were conducted.