News

Trump’s Ukraine Peace Strategy Projects American Weakness

On the third anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Donald Trump’s government is ramping up the pressure on Kyiv to sue for peace. Will this be like Vietnam and Afghanistan, where Washington cut and ran, too big to consider anyone’s interests other than its own? Or does Kyiv – and Europe – have options other than making peace on Trump’s terms? The authors, frequent visitors to Ukraine, outline the dangers and possibilities of current developments.

Paris in January 1973. Doha in February 2020. Saudi Arabia in February 2025 – all peacemaking summits with the same aroma and feel. But there are key differences before we believe that the stage is simply being set for another American episode of cut and run.

After years of promising never to abandon their close ally, Washington did just that with South Vietnam in Paris, and with the Government of Afghanistan in Doha. In both these wars, the US had contributed years of blood and treasure to propping up its ally. In both these “peace” processes – because a just peace was not the outcome – the ally was not even present as Washington negotiated the terms and set the pace of its exit from those conflicts, despite their prior investment.

The war in Vietnam cost America 58,000 lives at its conclusion and an estimated $1 trillion in today’s money; Afghanistan $2 trillion over 20 years, or $300 million per day, and 3,468 coalition military and 3,917 contractor deaths. This pales against the extent of local casualties: 600,000 excess deaths in Iraq, for instance, 170,000 in Afghanistan and 3.4 million during America’s phase of the war in Vietnam, if nothing else an indicator of the commitment on both sides.

So far, the Ukrainian war has cost − President Zelenskyy recently admitted − 43,000 military deaths and 198,000 wounded. Russian casualties are estimated at over 800,000, with the dead numbering perhaps a quarter of this grisly tally. International assistance to Ukraine has so far topped €267 billion, or €90 billion annually. This is without the hundreds of billions of dollars in physical destruction and expected reconstruction bills.

In Paris and Doha, the American administration agreed terms and a timetable to leave the country. There were side assurances to their allies, a nudge and a wink to stay the course. “You have my absolute assurance that if Hanoi fails to abide by the terms of this agreement, it is my intention to take swift and severe retaliatory action,” wrote Richard Nixon to South Vietnam’s President Nguyen Van Thieu over the talks on 14 November 1972. Saigon fell to Hanoi’s forces in April 1975.

“No, it is not,” said President Joe Biden when asked “Is a takeover of the Taliban now inevitable?” on 8 July 2021, just five weeks before the collapse of Ashraf Ghani’s government in Kabul, when it was clear to those of us in Kabul that without international support, the government would fold.

Similar pledge

Biden made a similar pledge to Ukraine. “You remind us that freedom is priceless; it’s worth fighting for as long as it takes. And that’s how long we’re going to be with you, Mr President: for as long as it takes,” he said to Volodymyr Zelenskyy in Kyiv on the first anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2023.

America’s war in Vietnam was, as Neil Sheehan puts it, an era so rich in characters, events, mendacity, cover-ups and other galumphing institutional nonsenses, so much like those in a work of fiction, that one is reminded of Philip Roth’s observation that it is difficult to be a fiction writer in America because reality is always outdoing the novelist’s imagination. This characterisation seems more apt than ever.

In a Truth Social post on 19 February, President Trump said: “a modestly successful comedian … A Dictator without Elections, Zelenskyy better move fast or he is not going to have a Country left. In the meantime, we are successfully negotiating an end to the War with Russia, something all admit only ‘TRUMP’ and the Trump Administration can do. Biden never tried, Europe has failed to bring Peace, and Zelenskyy probably wants to keep the ‘gravy train’ going. I love Ukraine, but Zelenskyy has done a terrible job, his Country is shattered, and MILLIONS have unnecessarily died – And so it continues ….”

Some of Sheehan’s “bright, shining lies”, employed by four American administrations from Dwight Eisenhower to Richard Nixon, including Nixon’s “secret” bombing of Cambodia − which was, of course, no secret if you were Cambodian or Vietnamese − would be harder today, given the relative transparency of modern media, though such lies today might be bolstered by “fake news” narratives.

As the Afghanistan Papers, published in 2019, showed, the tendency of US presidential administrations to lie to the American people and of military officers to go along with failing strategies due to a misplaced “can-do” attitude seems an enduring feature of the environment. What also has not changed today is the marginalisation of the real victims of war − both foreigners and Americans − and the way that leaders default to ducking and diving responsibility.

Bully Zelensky

Trump may just crudely (as is his wont) be trying to publicly bully Zelenskyy into being compliant. This is likely to be a difficult journey for which Trump does not have all the keys. Several traps lie ahead.

The first is in his mistake to sideline Europe, and in particular Turkey. Ukraine’s geographic position and size as the second-largest country on the European mainland (after Russia itself) at the heart of the continent puts it at the heart of security, unlike Vietnam or Afghanistan, the former relying on a flaky domino theory to justify external support.

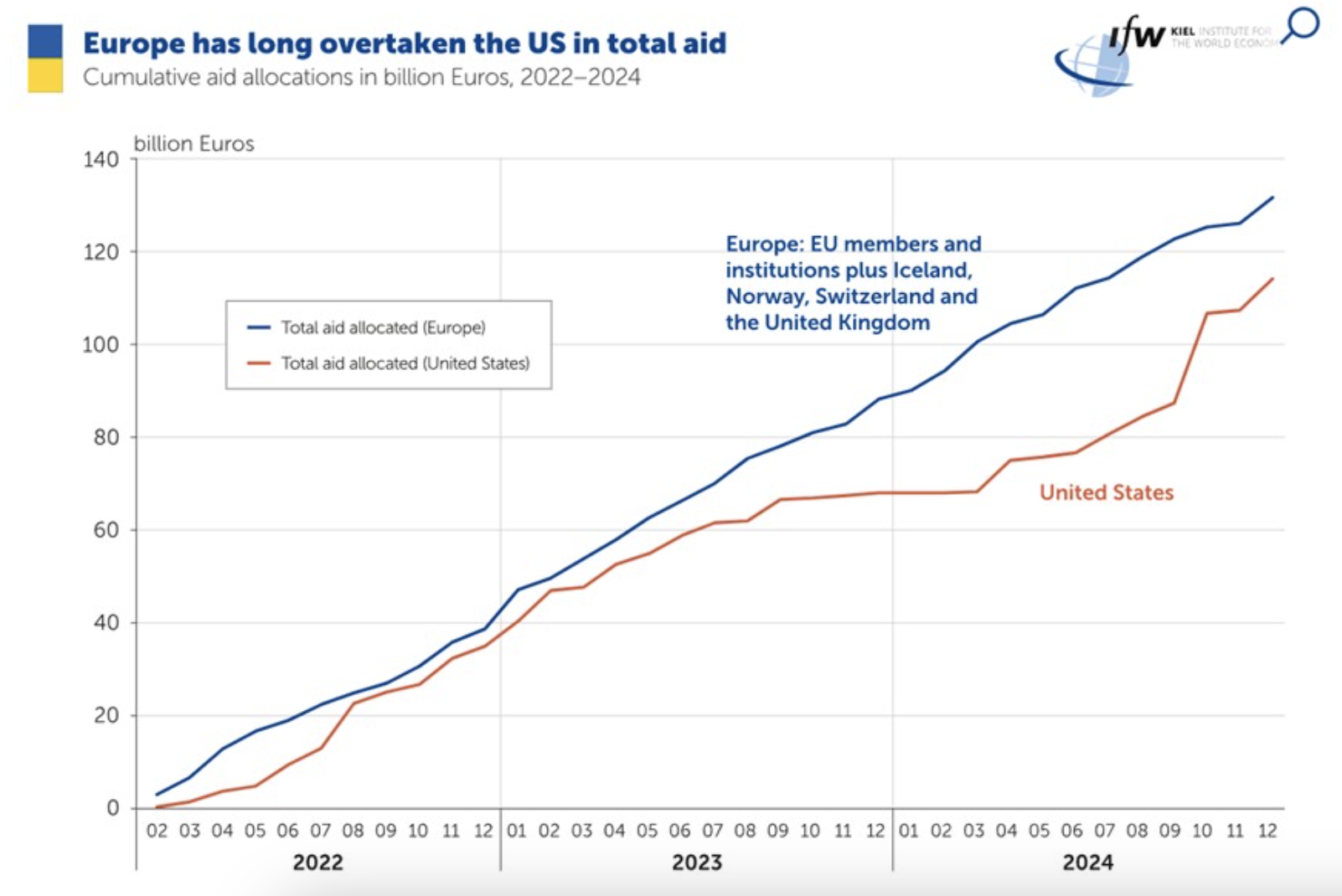

A second mistake is to overstate (again, not an uncommon trait) the United States’ power. While its military remains the steel backbone of NATO, this is not the Western alliance at Munich in 1938, another ominous parallel that has been played and replayed. Contrary to his arithmetic, European aid to Ukraine now outstrips that of the United States. Moreover, these volumes need to be disaggregated to provide a reasonable perspective not permitted by social media hyperbole. Around half of donor support goes to military assistance (much of which is spent by the donors themselves, of course), some 44% to financial support, and 7% towards humanitarian aid.

And relative to the likely costs of Ukrainian collapse, the investment is small, so far too small to stop Russia.

Germany, the UK, and the US, for example, have mobilised less than 0.2% of their GDP per year to support Ukraine, while other rich countries like France, Italy and Spain allocated just 0.1%, according to the Kiel Institute for the World Economy’s Ukraine Support Tracker. “Even small domestic policy priorities are many times more expensive than what is being done for Ukraine,” notes Kiel. Germany’s tax subsidies for diesel fuel (so-called “diesel privilege”) cost taxpayers three times more per year than Germany’s military aid for Ukraine.

“Political ‘pet project’”

‘When looking at the government budgets in most European donor countries, Ukraine aid over the last three years looks more like a minor political ‘pet project’ rather than a major fiscal effort,” says Christoph Trebesch, head of the Ukraine Support Tracker. This lack of commitment to do the job is shared by both Europe and the US, however, as is the absence of a plan beyond keeping Ukraine on life support – with just enough aid to survive and not enough to win.

Other calculations have Ukraine itself already meeting 55% of the costs of the war, Europe (and other non-US sources) some 25% and Washington 20%. If the US pulls back, the 20% will need to be shared between the non-US players, and obviously at least doubled. The threat of disconnecting Starlink is more problematic, but at least financially Europe could do it.

The most notable key difference between Ukraine, on the one hand, and Afghanistan and South Vietnam, on the other, is the will to fight. America is not fighting in Ukraine as it was in Afghanistan and Vietnam. It is enabling defence.

In September 1963, in response to a question posed by Walter Cronkite as to how the war in Vietnam was progressing, President JF Kennedy said: “I don’t think that unless a greater effort is made by the Government to win popular support that the war can be won out there. In the final analysis,” noted the President, “it is their war. They are the ones who have to win it or lose it. We can help them, we can give them equipment, we can send our men out there as advisers, but they have to win it, the people of Vietnam….”

Rule still held

More than half a century later, this rule still held. In 2015, then US Secretary of Defence Ash Carter said of the post-Saddam Iraqi Army’s ability to fight the Islamic State, “We can give them training, we can give them equipment − we obviously can’t give them the will to fight.”

There is no doubting the Ukrainian will to fight and defend their homeland. This commitment was early on epitomised by Zelenskyy’s now-famous reply, in stark contrast to President Ghani’s obvious weakness in Kabul, to an offer of evacuation in the early days of the war: “I need ammunition, not a ride.”

Statistics about aid, as the journalist Anne Applebaum has noted, “can never fully describe what happened”. They describe, at least in Ukraine’s case, how history rewrites the present. Stalin’s crimes include the terror famine of the Holodomor in Ukraine, which cost around five million lives, something that never lies far below the surface and drives Ukrainians’ sense of purpose, expressed in the extraordinary sacrifices made in this war.

The lesson of Afghanistan – for Afghans and the other allies and coalition partners of the United States – was the same as for the South Vietnamese in 1975: don’t trust Washington. America is too big, and too self-centred as a consequence, to include its allies in its innermost strategic counsels. The fact that allies were never privy to the side deals struck by US negotiator Zalmay Khalilzad with the Taliban is a case in point, just as the South Vietnamese were cut out of Kissinger’s deal-making with Hanoi.

The vagaries of Western support and the population’s predilection towards self-regard is a significant handicap in its foreign policy, not least in terms of stamina. The more unreliable Western support has become, the greater the political pressures inside Ukraine. While this may have a constructive effect, both on galvanising the military and peace process, it threatens to fracture Ukrainian domestic political unity, the opposite that Western supporters desire.

Not about charity

Western support to Ukraine is not about charity. It’s about upholding international law, protecting democracy and stopping Vladimir Putin from putting back together the Soviet system of brutal imperial government.

Trump’s exaggerated language over Ukraine will not be cost-free. It will cost the free world’s respect. This is precisely the opposite goal the President seeks. It will undercut the view of American reliability and the practices of mutual benefit. As Singapore defence minister Ng Eng Hen put it at the recent Munich Security Conference, America’s “image” abroad had “changed from liberator to great disruptor to a landlord seeking rent”. It shakes hitherto sacrosanct principles of international relations around sovereignty, out of which a slew of other conflicts could well emanate, not least in Africa with its arbitrary and weak borders. It could also catalyse a new arms race, especially to gain nuclear weapons, non-proliferation another post-1945 tenet now under threat.

This can only accelerate if the effect of Trump’s action is to break the transatlantic relationship as portrayed in NATO, which would suit Putin perfectly. And it would run counter to strengthening international systems to hold governments accountable for war crimes by effectively foreclosing on legal proceedings against the Russian forces who have committed, among other atrocities, acts of mass murder, rape, forced migration, ethnic cleansing, and child abductions. Washington’s early moves – including refusing the “war of aggression” language in the G7 statement) suggest that it is intent on closing down the war crimes issue.

While Trump likes to believe that he alone can make a deal, Washington may well discover that, on current form, Vladimir Putin is to be no more assuaged in his ambition to take over Ukraine than the Taliban were in Afghanistan or, for that matter, Hanoi with South Vietnam.

Worst of all worlds

As such, the West might end up, if Ukraine were to implode, with the worst of all worlds: an alienated and emboldened Russia and a seething, anti-Western Ukraine forced back within a neo-Soviet fold. The war is then likely to move to a different, unconventional phase. Ukrainians have learnt bitter lessons in entrusting their security to Moscow.

Whatever Trump may like to believe in his quest to cut a deal, the Western way of life, of democracy, liberal policy and the freedom of personal choice would be imperilled if Ukraine fell. If that were to eventuate as a consequence of his action (and inaction), President Trump would have placed himself firmly on the wrong side of history.

This article originally appeared on The Daily Friend