News

Rocket Man meet Drone Man – the Future of Combat

The tradition of Ukrainian aerospace continues. Driven today less by prestige than necessity, it has become a global leader in ‘kopters’ – as drones are locally known.

Former Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

Former Research Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

It’s a longstanding tradition. On this highway to Kyiv is a Soviet-era missile, a memorial to Sergei Korolev, born in nearby Zhytomyr more than 118 years ago, considered the father of the USSR’s rocket and space programme.

Korolev oversaw the early successes of the Sputnik and Vostok projects, including the first human Earth orbit mission by Yuri Gagarin in April 1961.

His was, however, not an easy ride.

An apparently difficult child from a broken family and having failed to be accepted to the prestigious Zhukovsky Academy in Moscow on account of his poor marks (a lesson in not peaking too soon), he attended the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute to train as an aircraft designer.

Arrested on a trumped-up charge during Stalin’s “Red Terror” (as a result of which at least 800,000 died between 1936-38) as a “member of an anti-Soviet counter-revolutionary organisation”, he was imprisoned for nearly six years, some of which was spent in a Siberian Gulag.

Rehabilitated through his work in a penal design bureau producing aircraft under Tupolev and Petlyakov during World War 2, he was officially rehabilitated only in 1957.

Korolev’s greatest skill was to be in strategic planning and organisation, especially necessary when, after the war, the Soviets integrated about 2,000 German aerospace and rocket scientists. This jump-started the Soviet programme, just as the Americans had done with Werner von Braun and his group, who moved to America under Operation Paperclip.

Despite his achievements being appropriated after his death in 1966 in the Soviet name, Korolev is today celebrated in his home town, with a small museum displaying the various achievements in the eponymous museum.

Visitors to the museum on a cold May day include wounded Ukrainian soldiers recovering from the bruising front line at a local hospital.

Aviation ingenuity

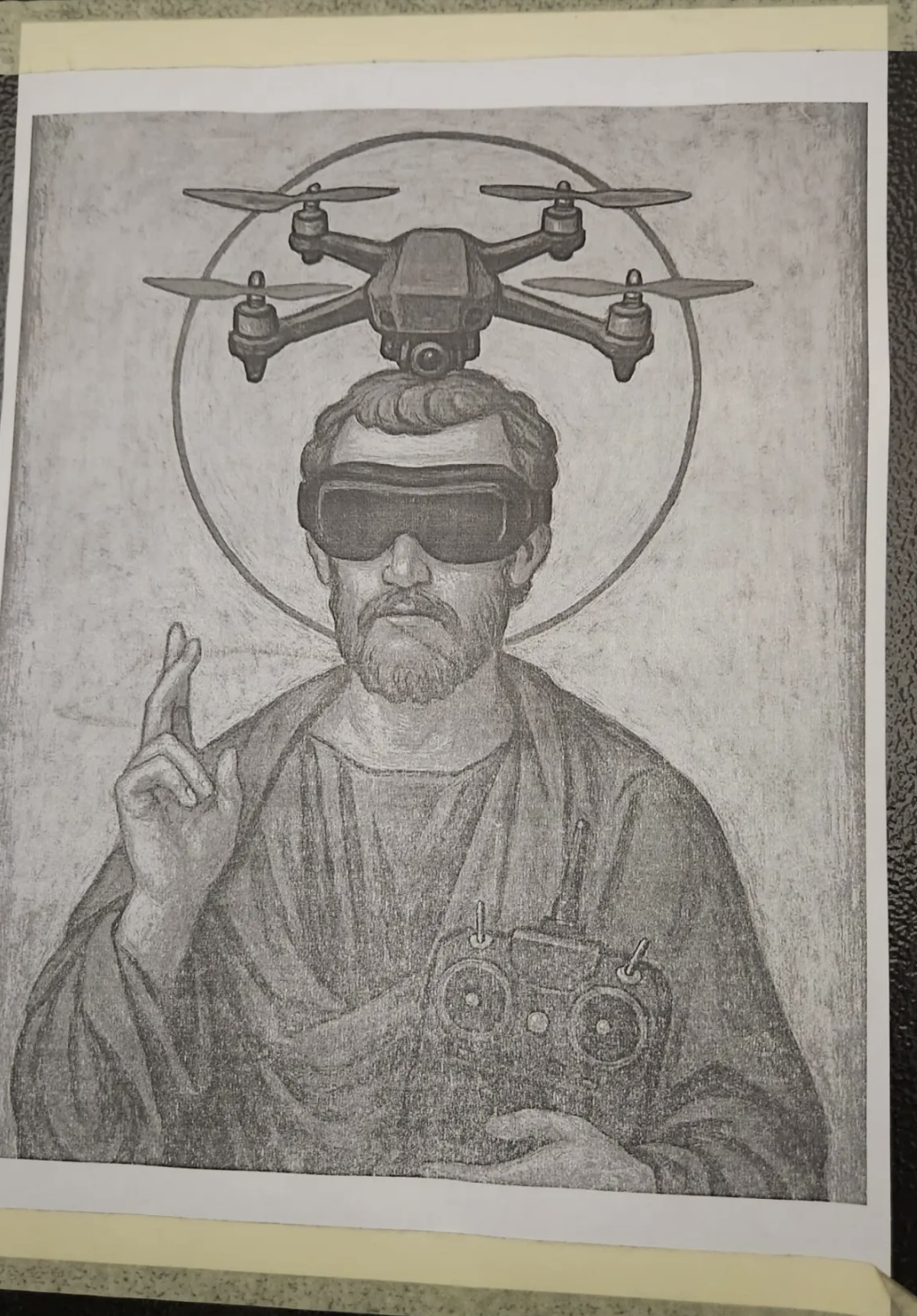

From Antonov to Korolev – a proud history in Ukrainian aviation. (Photo: Greg Mills)

The country’s aviation sector continues to boom, this time out of necessity in Ukraine’s struggle against its nemesis, Russia. The most famous name, Antonov, continues to produce, despite frequent missile interruptions, while its university centres of excellence churn out quality graduates in design and engineering.

Sasha, 35, is also a graduate of Kyiv Polytechnic, a head of R&D with SkyRiper, one of the leading drone manufacturers in Ukraine.

‘Hands and calculators’ – people and cost effectiveness – will win this war, say Ukrainians. (Photo: Greg Mills)

Driven by a shortage of artillery ammunition, Ukraine’s survival instinct and “horizontal interaction” between frontline units and the engineers back in Kyiv and other cities, Ukrainian production is now around 100,000 drones a month.

About 10,000 are used by frontline forces each day, and seven of 10 battlefield Russian casualties are caused by drones, a shift in technology which helps to offset Russia’s numerical population advantage.

“We all have friends and relatives at the frontline,” says Sasha, the leader of a youthful team (average age 22) of engineers. “They tell us all the time what works and what they need.”

Drones are now the great equaliser in Ukraine’s defence, a cost-effective way of making up the deficit in manpower, materiel and financing compared with their Russian foe. Whereas 155mm artillery rounds cost between $2,000-$7,000 each, depending on their spec, and a Javelin anti-tank missile $250,000, Ukrainian FPV (first person view) kamikaze drones are less than $500 apiece. With a range of the smaller carbon and alloy drone of up to 30km with a 4kg payload, this has effectively shrunk the 1,200km frontline.

FPV drones are being used at a rate of 10,000 a day in Ukraine. (Photo: Greg Mills)

The next generation of multicopter with up to 3.5 hours of flight endurance. (Photo: Greg Mills)

Handled by a team of just three soldiers, and with mission times of around 15 minutes, drones can be continuously cycled. “The frontline is now a 10km ‘grey zone’,” says the partner at SkyRiper, Anton, his 70-strong workforce delivering 10,000 drones a month from several sites around Kyiv.

“It’s a no-go area over which drones dominate.” Most armoured vehicles – sometimes requiring as many as 10 drone hits – are knocked out usually on the way to this no-man’s land.

While it makes great headlines, there is less technological focus on drone “swarming” than last-mile targeting, avoiding Russian efforts to jam signals (in part by increasingly employing fibre-optic technology), and focusing on improved lethality and manoeuvrability.

“The drones have to be capable of going into the forests, ducking under netting, looking for the weak spots in armoured vehicles,” he says. Anton cites Marx in keeping an eye on sophistication and cost: “In drone warfare, quantity has a quality. It’s better to have 100 drones than 10, which can swarm.”

At a general aviation airfield 45 minutes outside Kyiv, Ivan talks enthusiastically about his Buntar B3 drone, designed at the National Aviation University at Kharkiv and built at an underground site in the capital. Battery powered, the Very Short Take Off and Landing (VTOL) multicopter is capable of 3.5 hours’ endurance, with one operator capable of simultaneously controlling multiple reconnaissance drones using the Buntar Copilot system, operating safely from a position far behind the frontline.

For Russia with little love – racked and stacked for the frontline. (Photo: Greg Mills)

Drone capabilities have undergone a revolution since 2022, not least in terms of range, accuracy, cost, the networking of multiple feeds and survivability.

“There are hundreds of drone manufacturers in Ukraine now,” says Ivan, CEO of Buntar Aerospace and a serial entrepreneur, who joined the infantry after the 2022 Russian invasion and was wounded in the east. “Most of them are assembling small drones from imported parts.” The B3 is a carbon fibre machine designed for ease of operation and survivability, including a minimal radar signature.

They believe that eventually, with the pace of technological change, the drone industry will shake out to “no more” than a dozen major manufacturers.

“We don’t have the luxury of time,” says Sasha, who also serves as an officer in the Ukrainian reserves. “We have 15,000 to 20,000 drones on the frontline at any time. But the Russians have perhaps three times this number, even though their effectiveness is about 40% of each mission, half as good as we manage.”

Buffer for Europe

The survival instinct of Ukraine has not only helped to change the current circumstances, but may also change the future of war and defence. It seems likely that international investment in Ukraine will be driven less by acts of charity in future and the defence of democracy, than self-interest, in particular in its role as what former president Viktor Yushchenko, who led the Orange Revolution in 2004, describes as “Europe’s body armour”.

Viktor Yushchenko, President of Ukraine from 2005-10, who survived a poisoning attempt when contesting the 2004 election against the Russian-backed Viktor Yanukovych. (Photo: Greg Mills)

While it undergoes its own domestic arms revolution, Ukraine will simultaneously have to learn to splice itself into the practical defence of Europe: air and maritime, especially, as these domains disdain borders. Ukraine will need to get itself on to the accounting book, even if it isn’t formally part of Nato, as Finland and Sweden did well in the 1980s.

In the process, Ukraine has the opportunity to become a source of capability, not a market for it, to develop the most potent defence sector in Europe, fuelling its own coffers, providing deterrence capability and buttressing European combat power.

If it can manage this transition, to become not just one of the world’s leading developers and manufacturers, but also exporters, Ukraine will become tougher as a target while boosting its economy. This would demand more international capital investment, which means releasing the fetters on various controls. While there is a risk of acquisitions and compromise of intellectual property, the exchange would translate into another Ukrainian tether to the Western system.

“This war has changed,” says Captain Viacheslav Shutenko, Commander of the Unmanned Systems Battalion in Ukraine’s 44th Mechanised Brigade.

“In 2022, this war was … more or less classical. But, in three and a plus years,” he observed in May 2025, “this war is about technology, this war is about precision, and this war is about speed.

Unmanned systems are no longer an auxiliary. They are decisive on the battlefield. This is why to win, Ukraine needs more drones, more unmanned systems – we need scalable production of drones and uninterrupted supply of drones.”

Setting up a defence sector for mass production of the tech that’s been fundamental to their success, for their own use and for that of allies, lies at the centre of this approach. Without Europe and Ukraine working more closely together, the end of the war is likely, in the words of another rocket man, to “be a long, long time”.

This article originally appeared on the Daily Maverick